EXCLUSIVE: Americans have a low opinion of Congress — that’s not news. At just 13%, approval of Congress polls about as well as a colonoscopy and only slightly better than thermonuclear war.

But if Americans are frustrated by a legislature that seems incapable of action, imagine if Congress had forbidden itself from even talking about our nation’s hardest problems.

That’s what happened when John Quincy Adams, who was elected to the House of Representatives after his presidency in 1830, tried to debate the issue of slavery.

JARED COHEN, BESTSELLING AUTHOR TO RELEASE ‘LIFE AFTER POWER,’ NEW BOOK ON SEVEN FORMER PRESIDENTS

The House had what was known as the “Gag Rule,” which prohibited members from even raising the topic. But when Adams brought it up and his colleagues tried to kick him out of the House and silence him, the former president fought back. He refused to be canceled and let a culture of censorship keep him from saying what he knew was true.

When John Quincy Adams left the presidency, defeated after one term, he was the least popular commander-in-chief since his father.

Beaten by Andrew Jackson in 1828, former President Adams thought his political life was over.

This article is excerpted by special arrangement from “Life After Power” by Jared Cohen (shown here) — who reveals how others attempted to cancel John Quincy Adams, America’s sixth commander-in-chief, who served in the House of Representatives after he lost his re-election bid for the presidency. (Fox News Digital; Jared Cohen/Simon & Schuster)

At 61 years old, after having served as an ambassador, senator, secretary of state and president, there were no further heights to which the founding son could climb.

For 18 months, he wallowed at home in Quincy, Massachusetts, reading and trying his hand at tree farming, only to find that he didn’t have a green thumb.

He might have stayed in Quincy for the rest of his days. When a friend suggested to Adams’ wife Louisa that her husband consider re-entering politics, she responded, “There are some very silly plans going on here and God only knows in what they will end, but I fear not at all to my taste.”

In a much lower position, Adams found a much higher calling.

But when the party convention nominated him to represent Plymouth in the 22nd Congress, he won in a landslide, and President John Quincy Adams became Rep. John Quincy Adams, the only former commander-in-chief to serve in the House.

With victory in hand, he wrote, “Election as president of the United States was not half so gratifying to my inmost soul.”

AFTER THEY LEAVE THE WHITE HOUSE, WHAT SHOULD AMERICA DO WITH OUR EX-PRESIDENTS?

Adams wasn’t a slaveholder, and he knew slavery was evil, but he didn’t enter Congress as a crusading abolitionist.

He didn’t actually know what he wanted to do when he arrived on Capitol Hill. Upon seeing his old friend back in Washington, Kentucky Sen. Henry Clay jokingly asked how Adams “felt upon turning boy again in the House of Representatives.”

But in a much lower position, Adams found a much higher calling.

Bestselling author Cohen (left) writes that with a single question by Adams (right) during the latter’s post-presidential terms as a member of the House of Representatives — “Am I gagged or am I not!?” — Adams “inadvertently christened the new edict forbidding debates about slavery: the Gag Rule.” But Adams pushed back hard. (Fox News Digital; DeAgostini/Getty Images)

With the threat of civil war hanging over the capital, Congress had a tradition of avoiding the issue of slavery altogether — members were afraid of what would happen if they brought it up. But that didn’t mean the American people, on both sides, weren’t vocal.

Adams’ anti-slavery sympathies were well known, and more than 40,000 people had signed over 300 petitions on the issue addressed directly to him.

The right to petition is protected by the First Amendment, and Congressman Adams would read what the petitioners — many of them women’s groups or Christian societies — had to say, presenting their petitions on the House floor, much to the chagrin of the slaveholders in Congress. His colleagues were furious.

CRISIS ON COLLEGE CAMPUSES: WHAT UNIVERSITY PRESIDENTS CAN LEARN FROM THE FOUNDING FATHERS

Terrified by Adams’ advocacy and that he was bringing up the most explosive issue in the country, the slaveholders fought back and passed a resolution to forbid the issue of slavery from being discussed at all. Shocked, Adams cried out, “Am I gagged or am I not!?”

With that question, he inadvertently christened the new edict forbidding debates about slavery: the Gag Rule.

The rules didn’t hold Adams back. He would bring up the issue as often as he could in whatever way he could, protecting the First Amendment right to petition and hardening in his abolitionism over time.

John Quincy Adams, America’s 6th president, went on to serve for nine terms in the House of Representatives, from 1831 until his death in 1848. He is the only president to be elected to Congress after leaving the presidency. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

In an era of political violence, even duels on the House floor — and amid threats from one Southern congressman that he would cut Adams “from ear to ear” — the former president defied his foes at great risk.

Upon reading about his exploits, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote admiringly that Adams was “no literary gentleman, but a bruiser … [H]e must have sulfuric acid in his tea.”

Just because the House had passed the Gag Rule didn’t mean Adams was powerless.

He pushed back in his own ways, calling a pro-slavery attempt to annex Texas “a war of conquest.”

Just because the House passed the Gag Rule didn’t mean Adams was powerless.

He denounced the reintroduction of slavery to a territory where it had been previously abolished and delayed the admission of another slave state, which would have tipped the balance of power in the Senate.

In the Amistad case, he represented enslaved men and women who had escaped their captors before the Supreme Court, winning them their freedom.

His argument relied on appeals to the court’s memory of the Founding Fathers, and he pointed to a copy of the Declaration of Independence hanging on the wall of the chamber, beseeching the justices, “If these rights are inalienable, they are incompatible with the rights of the victor to take the life of his enemy in war, or to spare his life and make him a slave.”

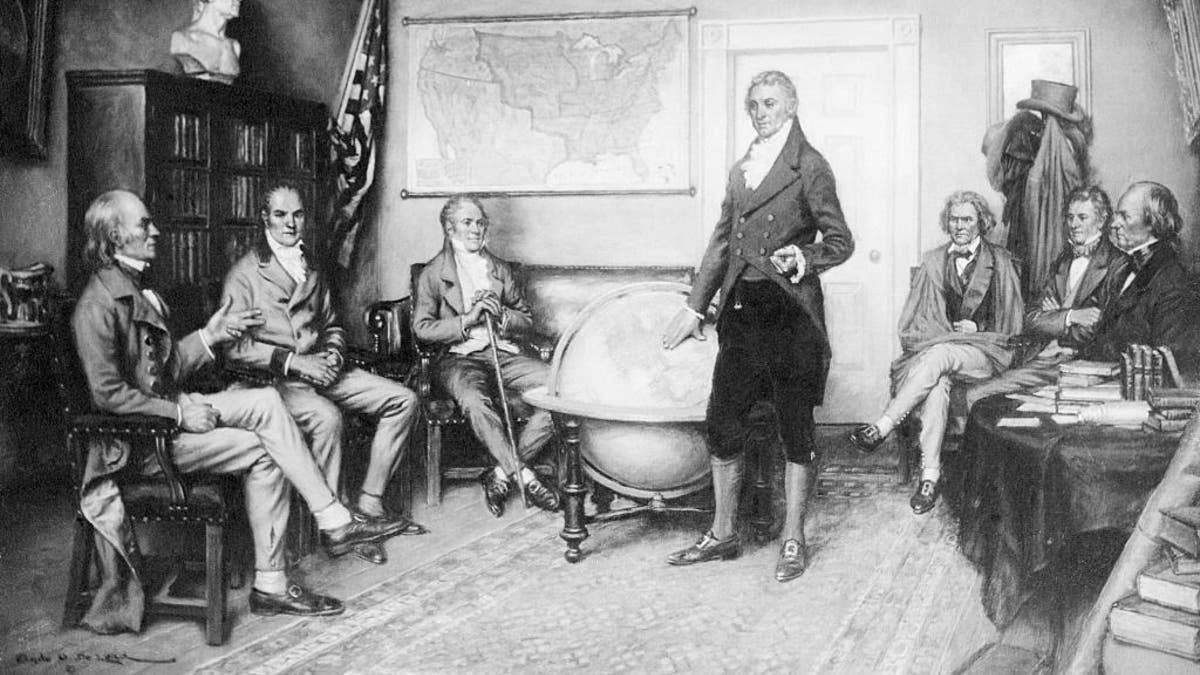

Illustration depicting the birth of the Monroe Doctrine. James Monroe is shown standing beside a globe; John Quincy Adams is shown seated at left. From a painting by Clyde O. DeLand. (Getty Images)

Rep. Adams left his mark in other ways, too.

He headed a 13-member select committee to investigate whether President John Tyler should be impeached — the first such committee in American history.

Adams also helped establish the Smithsonian Institution.

By the time Adams got the Gag Rule repealed in 1844, he’d done more than make history as the only former president elected to the House of Representatives. He’d become the leading abolitionist in Congress in the first half of the 19th century.

Today’s elected representatives can make a difference by reminding Americans of our nation’s finest traditions.

He’d tied the cause of abolition to the purpose of the American founding, using his authority as the son of a Founding Father and his knowledge and experience in government to become an elder statesman, even as a junior member.

When he died in 1848 at age 80 in the halls of the Capitol, he was described as “a living bond of [connection] between the present and the past.”

Upon his death, Adams passed the torch of abolition to a young member of Congress, Abraham Lincoln, with whom he overlapped during one term, and who served on the committee to arrange Adams’ funeral.

Abraham Lincoln, while he was still a young congressman prior to his election to the presidency, served on the committee to arrange the funeral of John Quincy Adams, America’s sixth president and a longtime member of Congress after that. (Painting by J.L.G. Ferris)

Adams didn’t let his frustrations at defeat in 1828 get the best of him, and he didn’t let his more powerful colleagues silence or cancel him.

Against odds much tougher than today’s Congress is facing, Adams moved the needle toward the principles of the American founding.

He was respected, but he wasn’t always popular. His frustrated opponents once said of him that he was the “acutest, the astutest, the archest enemy of Southern slavery that ever existed … the Old Man Eloquent, John Quincy Adams.”

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Today, members of Congress can make a name for themselves on television or on social media, using their positions as platforms and becoming talking heads rather than legislators.

Or they can make a difference by standing for first principles and reminding Americans of our nation’s finest traditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR LIFESTYLE NEWSLETTER

If they do that, maybe they’ll restore Americans’ faith in our institutions, and they’ll follow in the footsteps of the great statesmen who came before them.

Excerpted from “Life After Power: Seven Presidents and Their Search for Purpose Beyond the White House,” © copyright Jared Cohen (Simon & Schuster, Feb. 2024), by special arrangement. All rights reserved.

Stay tuned for additional excerpts at Fox News Digital from the new book “Life After Power.”

For more Lifestyle articles, visit www.foxnews.com/lifestyle.