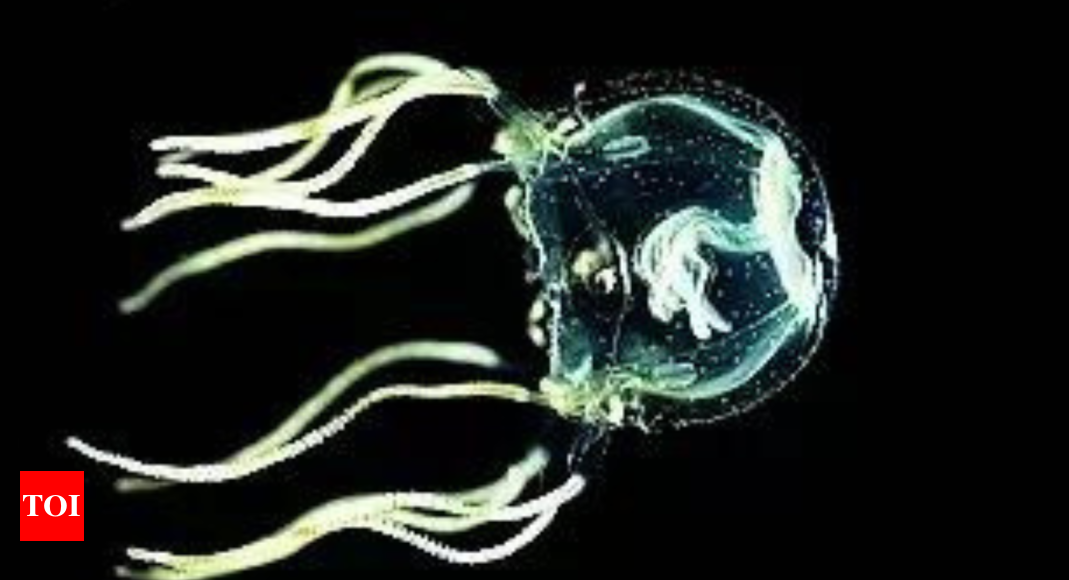

In the dappled sunlit waters of Caribbean mangrove forests, tiny box jellyfish bob in and out of the shade. They are distinguished from true jellyfish in part by a complex visual system – the grape-size predators have 24 eyes. But like other jellyfish, they are brainless, controlling their bodies with a distributed network of neurons.

That network, it turns out, is more sophisticated than you might assume. On Friday, researchers published a report in Current Biology indicating that the box jellyfish species Tripedalia cystophora have the ability to learn. Understanding their cognitive abilities could help scientists trace the evolution of learning.

The tricky part about studying learning in box jellies was finding an everyday behavior that scientists could train the creatures to perform in the lab. Anders Garm, a biologist at the University of Copenhagen and an author of the new paper, said his team decided to focus on a swift about-face that box jellies execute when they are about to hit a mangrove root. These roots rise through the water like black towers, while the water around them appears pale by comparison. But the contrast between the two can change as silt clouds the water and makes it more difficult to tell how far away a root is. How do box jellies tell when they are getting too close? “The hypothesis was, they need to learn this,” Garm said. “When they come back to these habitats, they have to learn, how is today’s water quality?”

In the lab, researchers produced images of alternating dark and light stripes, representing the mangrove roots and water, and used them to line the insides of buckets about six inches wide. When the stripes were a stark black and white, representing optimum water clarity, box jellies never got close to the bucket walls. With less contrast between the stripes, however, box jellies immediately began to run into them. This was the scientists’ chance to see if they would learn.

After a handful of collisions, the box jellies changed their behaviour. Less than eight minutes after arriving in the bucket, they were swimming 50% farther from the pattern on the walls, and they had nearly quadrupled the number of times they performed their about-face maneuver. They seemed to have made a connection between the stripes ahead of them and the sensation of collision.

Going further, researchers removed visual neurons from the box jellyfish and studied them in a dish. The cells were shown striped images while receiving a small electrical pulse to represent collision. Within about five minutes, the cells started sending the signal that would cause a whole box jellyfish to turn around. “It’s amazing to see how fast they learn,” said Jan Bielecki, a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Physiology at Kiel University in Germany, also an author of the paper.

Researchers who were not involved in the study called the results a significant step forward in understanding the origins of learning. “This is only the third time that associative learning has been convincingly demonstrated in cnidarians,” a group that includes sea anemones, hydras and jellyfish, said Ken Cheng, a professor at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia.

In future work, researchers hope to identify which specific cells control the box jellyfish’s ability to learn from experience. Garm and his colleagues are curious about the molecular changes that happen in these cells as the animals incorporate new information into their behaviour. They wonder whether the capacity to learn is universal among nerve cells, regardless of whether they are part of a brain. It might explain their peculiar persistence in the tree of life.

That network, it turns out, is more sophisticated than you might assume. On Friday, researchers published a report in Current Biology indicating that the box jellyfish species Tripedalia cystophora have the ability to learn. Understanding their cognitive abilities could help scientists trace the evolution of learning.

The tricky part about studying learning in box jellies was finding an everyday behavior that scientists could train the creatures to perform in the lab. Anders Garm, a biologist at the University of Copenhagen and an author of the new paper, said his team decided to focus on a swift about-face that box jellies execute when they are about to hit a mangrove root. These roots rise through the water like black towers, while the water around them appears pale by comparison. But the contrast between the two can change as silt clouds the water and makes it more difficult to tell how far away a root is. How do box jellies tell when they are getting too close? “The hypothesis was, they need to learn this,” Garm said. “When they come back to these habitats, they have to learn, how is today’s water quality?”

In the lab, researchers produced images of alternating dark and light stripes, representing the mangrove roots and water, and used them to line the insides of buckets about six inches wide. When the stripes were a stark black and white, representing optimum water clarity, box jellies never got close to the bucket walls. With less contrast between the stripes, however, box jellies immediately began to run into them. This was the scientists’ chance to see if they would learn.

After a handful of collisions, the box jellies changed their behaviour. Less than eight minutes after arriving in the bucket, they were swimming 50% farther from the pattern on the walls, and they had nearly quadrupled the number of times they performed their about-face maneuver. They seemed to have made a connection between the stripes ahead of them and the sensation of collision.

Going further, researchers removed visual neurons from the box jellyfish and studied them in a dish. The cells were shown striped images while receiving a small electrical pulse to represent collision. Within about five minutes, the cells started sending the signal that would cause a whole box jellyfish to turn around. “It’s amazing to see how fast they learn,” said Jan Bielecki, a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Physiology at Kiel University in Germany, also an author of the paper.

Researchers who were not involved in the study called the results a significant step forward in understanding the origins of learning. “This is only the third time that associative learning has been convincingly demonstrated in cnidarians,” a group that includes sea anemones, hydras and jellyfish, said Ken Cheng, a professor at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia.

In future work, researchers hope to identify which specific cells control the box jellyfish’s ability to learn from experience. Garm and his colleagues are curious about the molecular changes that happen in these cells as the animals incorporate new information into their behaviour. They wonder whether the capacity to learn is universal among nerve cells, regardless of whether they are part of a brain. It might explain their peculiar persistence in the tree of life.